It’s Week 2 of my Yale class on Courage in Theory and Practice, and we talked about the Hero’s Journey, and heroism in general. I also had the chance to discuss it afterwards with Producer Vic, and we recorded our conversation as a podcast – see the bottom of this blog post for the details of the audio and video versions. You can find the slideshow from my lecture here on Slideshare. In case you want to take a look at the reading list, here it is again: GLBL252 Courage Syllabus.

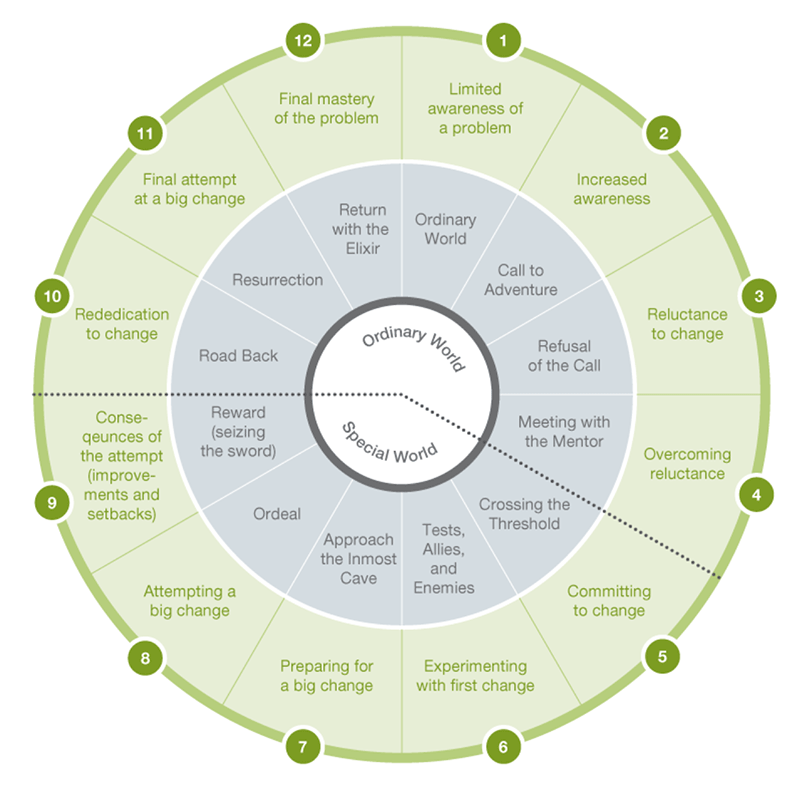

The Hero’s Journey was documented in Joseph Campbell’s 1949 book, The Hero With A Thousand Faces, in which he set out the classic narrative structure (or “monomyth”, as he called it) that has dominated storytelling since time immemorial, from the oral traditions through mythology and fairy tales to modern day novels and movie plotlines. George Lucas, the film director, was a good friend of Joseph Campbell, and the plot of his original Star Wars movie exactly follows the Hero’s Journey arc, illustrated below.

The majority of plots broadly follow this model of Setup – Confrontation – Resolution, which seems to resonate with something in the human psyche; we admire people or characters who have voluntarily or forcibly departed from the status quo, faced great challenges, and emerged as a better person. Possibly we want to believe that we, too, can go on an incredible journey and come back transformed for the better.

Some thoughts on this – some from my own head, others arising from our class discussion:

At the outset, the hero isn’t a hero

Crucially, if we aspire to heroism yet know ourselves to be currently very sub-heroic, the hero is not a hero at the start of the story. This gives us hope that, given the right circumstances and the call to adventure, we might also be able to transcend our current limitations and discover, if not exactly superpowers, at least latent talents that we can use to serve the greater good.

Why do we create heroes?

Other species may have alpha males or queen bees, but as far as we know, humans are the only species that creates heroes. Why do we do it?

I’d be interested in your views – for now, my working theory is that we feel some sense of awe and wonder when we witness exceptional behaviour – be it courageous, athletic, artistic, intellectual, or moral. Psychologists have documented the uplifting effect of witnessing acts of extraordinary altruism, so it seems logical by extension that other forms of heroic behaviour could create the same effect.

You are the average of the 5 people you spend the most time with

As the entrepreneur Jim Rohn said, “You are the average of the 5 people you spend the most time with,” and I think this can apply at least as much to the people we “spend time with” in books, TV series, online, and in the media. I’m sure you have occasionally had the privilege of reading a book that fundamentally changed the way you saw the world, at least for a few days, as a result of you “spending time with” that author, and being exposed to their worldview.

As the entrepreneur Jim Rohn said, “You are the average of the 5 people you spend the most time with,” and I think this can apply at least as much to the people we “spend time with” in books, TV series, online, and in the media. I’m sure you have occasionally had the privilege of reading a book that fundamentally changed the way you saw the world, at least for a few days, as a result of you “spending time with” that author, and being exposed to their worldview.

Statistics show that if most of your friends are overweight, chances are that you will be too. By the same token, divorce can appear contagious – once one couple in a social group splits up, others often follow suit. Norms and baselines shift in response to our peer group.

This is why I’m limiting the amount of time I spend on news sites, as I was in danger of certain politicians getting into my top 5, and I didn’t want them mixing into my average.

So, one way and another, when we “spend time with” heroes and moral exemplars, they lift us up and raise our sights.

Heroism as an excuse

One opposing view was that, by labelling such people “heroes”, we let ourselves off the hook. “She is such a hero, volunteering to help victims of x in country y.” By calling them heroes, we set them apart from us mere mortals, thus conveniently absolving ourselves from attempting to match their high standards of behaviour.

I’ve been guilty of this latter attitude myself. I used to think that there were “people like that” who were capable of epic adventures like climbing mountains or trekking to poles, and I was definitely not one of them. But then I met Dan Byles, who had rowed across the Atlantic with his mother. His mother! That disrupted my view of what kind of people had adventures (absolutely no disrespect to Dan’s mother, Jan, who is a remarkable woman)…. and that disruption ultimately led to me having an adventure or three of my own. I have now had people say to me, “oh, you’re one of those”, meaning, “you’re not like me”, which absolutely makes me want to scream. “People like me” can become “people like that” – all you need is the self-belief and the motivation.

So I’d like to invite you, if you have a stereotype of “people like that” who do great things, find an example that breaks the mould. Find someone like you who has done something like that. Disrupt your own opinion of what it takes to do something heroic. And see if it could be you.

Heroism is a feminist issue

This was when the conversation got even more interesting. The sociologist Michael Kimmel wrote in 1996 that gender must be made visible to men since, “we continue to treat our male military, political, scientific or literary figures as if their gender, their masculinity, had nothing to do with their military exploits, policy decisions, scientific experiments, or writing styles and subject”. And it is true that heroism – in men and women – tends more usually to be associated with acts of masculine strength and robustness, rather than the more subtle feminine kinds of heroism.

This is most blatantly clear if you google on “action heroes”, for it seems that by definition “action” has to involve at least a very large gun, and preferably a shoulder-mounted rocket launcher. Even the female action heroes are heavily armed. These films are massive commercial successes, so I don’t suppose it would cut much ice with studio execs to ask if, from a moral perspective, this is really the kind of heroism we should be endorsing.

Even when we hail political or corporate leaders as heroes, there is an implicit gender bias. These are areas in which women are still vastly under-represented, largely because the character traits that are recognised and rewarded in these worlds are still predominantly masculine. The more feminine traits, like collaboration, negotiation, nurturance, and quiet wisdom are, I think, gaining in currency, but there is still a long way to go.

There are, of course, notable exceptions. “To Kill A Mockingbird” was a beautiful example of the best kind of hero; Atticus Finch epitomised integrity, intelligence, high moral standards, humanity, justice, and good parenting. Finch heads up this online list of The 7 Most Moral Characters on Film – sadly, most of the films are in black and white, which maybe says something rather damning about current trends in entertainment.

Where should we set the bar on heroism?

Like so many superlatives, “hero” has become cheapened through over-use. When I googled recent news stories with “heroes” in the headline, I was surprised and pleased to find that the word is still generally used in relation to genuinely impressive feats (see my slideshow for examples). But in everyday usage, anything from providing bagels for a brunch to sharing a friend’s article on Twitter can earn us the accolade of “hero”.

One of my colleagues at the Jackson Institute told me about an incident when he was testifying to a government committee, and doctors helping treat patients during the Ebola outbreak in Africa were being hailed as heroes. My colleague stood up and offered his view that the risks facing the doctors were minimal, and they were simply doing the job that they had been trained and paid to do. His comments were not universally welcomed, but he was trying to ensure that attribution of heroism should be reserved for those who had gone well above and beyond the call of duty.

Though I agree with my colleague’s view, at the same time I would like to suggest that we can all be the hero of our own lives, and that by thinking of ourselves this way, we can give ourselves the inner strength and resourcefulness to act more courageously.

Here are a couple of exercises I set for my students, which you may like to try:

Exercise 1

Who are the five people you spend the most time with (in real life, online, in the media etc)?

What would the average of those five people look like?

Is that the person you want to be?

Exercise 2

Think of a story from your past when you were at your most “heroic”.

In 100-200 words, write the story as you normally would.

In 100-200 words, write it as a heroic tale, focusing on the emotions, qualities, and strengths that elevate it from the everyday to the exceptional. This may feel rather strange, but really hype it up as much as you can.

Now write about something audacious you want to do in the future, using the heroic style.

You may also want to consider: What would be your monsters? What would be your kryptonite? How can you be heroic in relation to those when the need arises?

Podcast details

YouTube iTunes RSS (Android users can enter the link into their podcast client and subscribe directly)

In case you want to take a look at the syllabus, here it is: GLBL252 Courage Syllabus.

Other Stuff:

On the evening of Friday 10th Feb, I will be giving a lecture at Darwin College, Cambridge. The lecture is titled Extreme Rowing, and is open to the public. Details here.

On Tuesday Sky News was running a feature on plastic pollution in the oceans, and I did a short interview via Skype. I don’t seem to be able to find it online, but maybe you’ll have better luck!

Hi Roz

Good to see starting your blog again.I am very happy that I consistently apply things which I wrote to your blog.For example bike to work,keeping gratitude journal with bliss app.Thank you for helpful,insigthful blogs.I will look forward to see them

Good for you, Akif – and thank you!